History

Iron Age

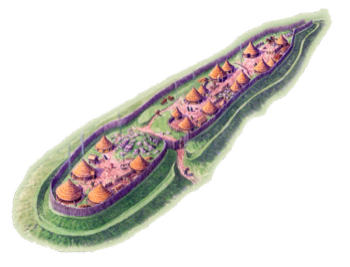

The earliest evidence of human settlement at Ruperra is from between around 700 BC and 100 AD, when an Iron Age Hill Fort was constructed along the ridge of Coed Craig Ruperra. The splendid panoramic views from the top of the ridge would have given the site a strategically strong position. Defensive banks and ditches are still visible around the area of the mound.

This hill fort lies within what would have been the tribal territory of a people the Romans called the Silures, who were a fiercely independent nation inhabiting the Vale of Glamorgan, Gwent and the valleys. The Roman historian Tacitus describes them as short, dark, curly-haired people more like those of North Africa than other Britons. This has led some to theorise that they may have been descendants of the ancient, pre-Celtic people of Britain.

Norman period

About 1100 AD a huge heap of earth for a Norman type motte or castle was piled up on the top of the ridge. On the top of the motte a wooden castle would have stood, ensuring a good defensive outlook over the surrounding countryside. The castle, of which nothing remains, is thought to have been part of the Norman takeover of south east Wales, falling into disuse once Caerphilly Castle was built in 1274. There is also a theory that the Welsh could have built the wooden castle to stop the Norman takeover. It is one of three local mottes, the others being the original Castell Coch and Castell Morgraig (the ruins of the latter are located behind the Traveller’s Rest pub on Caerphilly mountain).

Adjoining Coed Craig Ruperra at the south-eastern end is a field where a geophysical resistivity survey was carried out in July 2004, to see if any traces of the site of an old chapel could be found. The survey results tentatively suggested not only the chapel but several buildings grouped around a central space which would indicate a great deal of agricultural activity probably during Norman times.

Iron Age Hillfort

circa 700BC - 100AD

Norman Motte and Bailey

circa 1100 AD

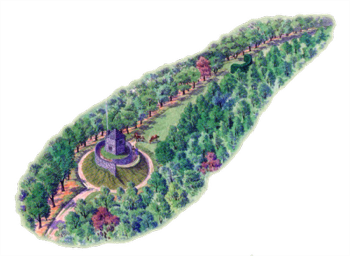

Garden and Summerhouse

circa 1700 AD

Georgian era.

Ruperra Castle was built in 1626 by Sir Thomas Morgan, who was one of the most powerful men in Wales at the time, being steward to the Earl of Pembroke. His wife Mary (who was related to the Lewis’ family of Y Fan, Caerphilly) had inherited her family’s medieval house and land at Ruperra. Full details of the history of Ruperra castle and the Morgan family are available on the website of the Ruperra Castle Preservation Trust at: https://www.ruperracastle.wales/ .

Coed Craig Ruperra was part of the castle estate. Both the Motte and the Hill Fort are part of what would have been a walk from Ruperra Castle gardens. Along the way, other features included the ‘Lights’, five clearings cut through the trees above the Castle to afford the walker a view of the parkland and the landscape beyond. The woods had not been wholly given over to the leisure pursuits of the rich, however – references in records to a “Ruperra woodyard”, and to coppicing and charcoal burning in the woods from the 16th – 18th centuries, show that it was also very much a working environment.

Medieval period

Little is known about the history of Ruperra during the medieval period although the first substantial dwelling on the estate was thought to have been built by Gwilym of Rhiwperra.

An intriguing article in Country Life in 1986 [Oct. 23 pp 1277-9] quotes a letter of one Rev. W Watkins ca. 1762, in which is recorded the bizarre discovery of an erect skeleton in a room 2.5m square during the digging of the foundations of a summerhouse at Ruperra. [Catalogue of MSS Relating to Wales in the British Museum, ed. Edward Owen (1922), IV p.847]. It has been speculated that this could be the skeleton of a certain Cadwgan, born around 1430, who was reputed to be an illegitimate son of Gwilym of Rhiwperra. Little is known of this person, apart from a reference by the antiquary George T Clark in his 1886 work on Welsh geneaology, Limbus Patrum Morganiae et Glamorganiae to the effect that ‘Cadwgan built and died in the tower long called after him at Rhiwperra’. Other than this reference, there is very little written about the fate of the ridge from medieval times onwards, until an estate plan of 1764.

The Lower Summerhouse

The remains of what we call the ‘lower summerhouse’ is situated on a path that originally led from the woodland to the castle gardens, via a gateway in the castle perimeter wall. This path was cleared and re-laid with the very welcome help of a group of volunteers from Rolls-Royce in 2007. The path runs in front of the building, and would have commanded splendid views over the eastern part of the Ruperra Estate and the countryside beyond. The path exits the woodland onto the drive at the back of the castle, directly opposite a wooden door into the castle grounds and next to a little rectangular building set in the wall. The lower summerhouse was obviously intended as a less arduously achieved pleasure place for the family at the castle than was the upper summerhouse.

After careful clearance and conservation work, the remains of this small summerhouse today consist of the remains of the pretty cobbled floor. This extended in squared patterns beyond the covered area of the building, and had slabs of stone inset for wooden pillars to support the roof – whether tiled or thatched is not yet determined. The front of the building was open and is a good example of the ‘rustic’ style of Georgian garden design. Behind the summerhouse is a large area of attractive rock, reaching up to the southern escarpment of the motte and possibly enhanced by landscape designers to illustrate the ‘picturesque‘ style.

The ruins of this building show that it was constructed in the late 18th / early 19th century of bricks similar to those used originally to build the castle and very probably made of local iron-rich clay. Originally there were wooden slats or timbers set into the bricks to support panelling and seating inside the structure. When the wood rotted, they were replaced at a later date by yellow engineering bricks. Iron nails found at the back of the building indicate that the outside also was covered with wooden panelling.

Upper Summerhouse - 17th Century

Further up the ridge, if you climb the spiral ramp to the top of the motte, you will find yourself standing on the very substantial and impressive footings of what would have been, two and a half centuries ago, a six metre square tower with walls just under a metre thick, which are presumed to be the foundations of the first summerhouse on the mound shown in a 1764 estate map of Ruperra. They would have easily supported the two-storey stone building described. An area of a superstructure, probably a fireplace, laid on these foundations was constructed of bricks and mortar similar in fabric, size and composition to those used in Ruperra Castle itself and this suggests that the first summerhouse was built in the 17th rather than the 18th century. This is borne out by the estate map of 1764 which describes the walls surrounding the summerhouse as having been built ‘sometime in the last century’. Some surviving plasterwork indicates a doorway in the south wall. The stone roof tiles and the blue-green window glass found around the mound must be from this structure.

Nothing of the early structure remained by the end of the 19th century: it may have been used to fill the ditch on the eastern side when the later wooden structure was erected. Some of the bricks may also have been taken from the site for re-use, possibly for the lower summer house.

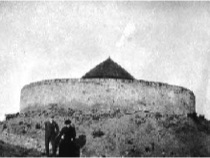

Upper Summerhouse - Victorian

Still visible on the motte are the remains of a later summerhouse consisting of three sides of octagonal sandstone kerbing with pitched pebble flooring and an inner area surfaced with calcite chippings. This is known to have been a wooden structure which was open to the south and was set inside the footings of the earlier building.

A photograph taken around 1918 to 1920 (left, bottom right), probably from the west, shows just the roof of the summerhouse from below the mound. Some local residents and soldiers from the war years still remember the building with its thatched roof intact and recall that the walls were constructed of split logs and open on one side (presumably the south) and that there were seats going around the inside. There was also a little white wooden gate at the top of the spiral path up to the summit.

No trace of the wooden walls, roof or seats of the summerhouse have survived although blacksmith-forged iron nails, clay pipe stems and some small pot-shards dating from that time have been found scattered over the site. Some more ‘modern’ oval iron nails made by the drawn wire method may indicate later 20th century repairs.